Introduction

The pandemic dramatically changed our individual and collective experience of towns. Opportunities to shake up or, better, transform our daily environments are on the urban agenda. Have we found our towns again?

Changed perception of public space invites new uses and activities onto our town centre streets and buildings. Renewing residential life is the challenge; innovative urban design makes modest first incursions with alternative uses of parking spaces – ‘parklets’; temporary opportunities in empty shop units – ‘meanwhile uses’; painting of road surfaces; planters to help change the character of ‘people places’. The south west Wales county of Ceredigion’s ‘Safe Zones’ project takes the opportunity to enhance the pedestrian and cyclist environment, support local businesses and reduce traffic dominance of public space [Figure 1]. Cardiff, in the early pandemic lockdown days, refocused the historic A48 on Castle Street towards people (including on bikes) and business, rather than cars – sadly recinded, to considerable public protest, as we write. [Figure 2]

Urban Design’s concept of ‘mixed use town’ has found its time.

This snapshot revisits towns in South Wales to encourage a renewed perception of urban spaces and development – a rediscovery of people-oriented town. En route, urban approaches to enhance our ‘people places’ are offered – long and short term, sometimes temporary, to help pursue rediscovery and renovation.

There is always more detail. For now, we set out some fundamentals of the rationale.

Social and economic vitality of town life depend on:

reasons to be there,

reasons to stay a while, and

a feeling for local character.

People and businesses demand a wide variety of activities and resources to meet their needs and aspirations. Residents living there, in good numbers, actively partake of their environments and are proud and pleased to help you enjoy their town. They are by far the best catalysts. Quality buildings and public spaces nourish that demand.

Jane Jacobs advises, “For illustrations, please look closely at real cities. While you are looking, you might as well also listen, linger, and think about what you see.” [1] Here, we consider qualities, strengths, attributes, and weaknesses of six towns in South Wales, to help identify immediate targets within rediscovered strategic rationales.

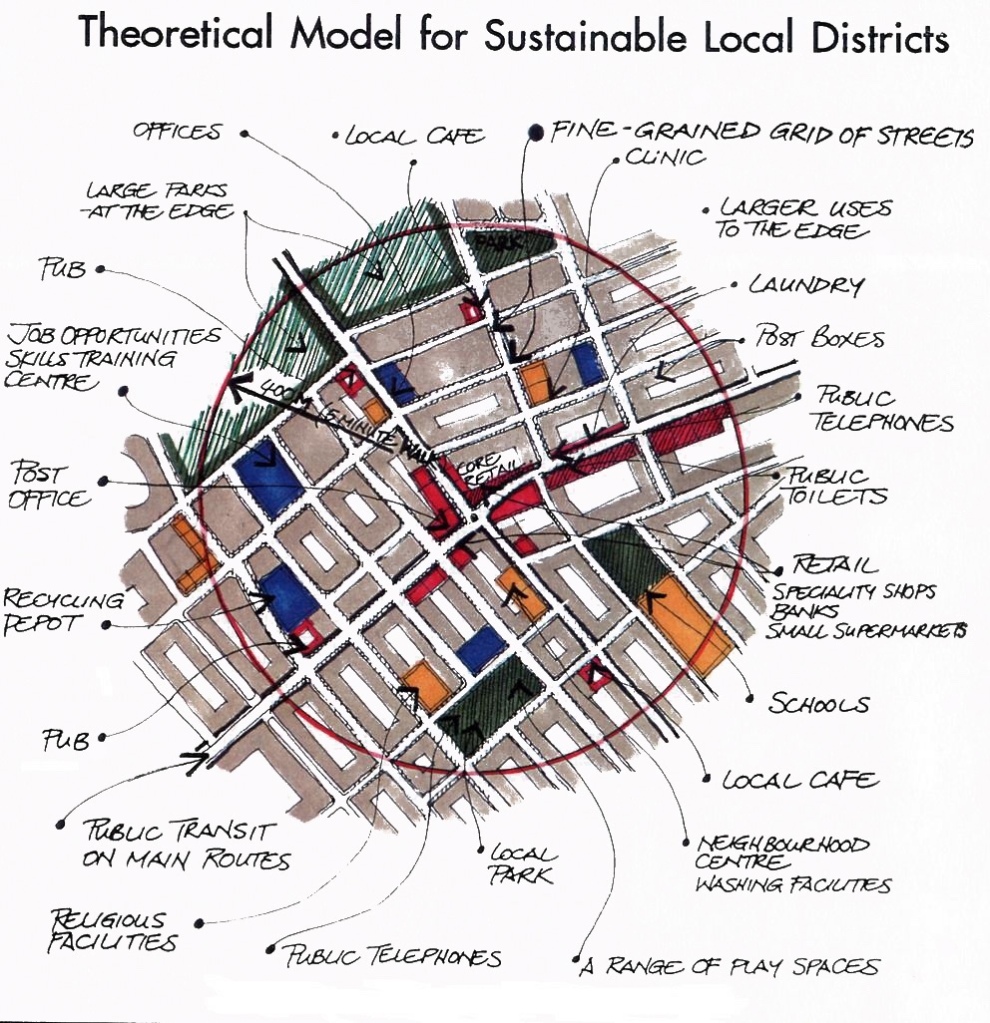

Alongside the many valued ingredients of neighbourhoods, the theoretical model introduces three key aids to ‘how we live’ – residential density, connectivity, and walkability. From the front doors of homes in the town centre or suburban ‘walkability circle’ [Figure 3], people can access the resources that constitute everyday life. ‘Basic daily needs’ include public transport, access to the jobs market, to regional resources and other activities not immediately available. The links to get there are nearby, ideally within 5 or 10 minutes walk from home or from where you arrive in town.

Viability, socially and commercially, requires people numbers – or lots of subsidy. Busy, bustling town, like the 17 pubs and all the other diverse resources available in the centre of Port Talbot before clearance and renewal, or in Swansea prior to the 1941 blitz and ‘slum clearance’, is based on residential density. People numbers are great for business.

In London, Glasgow, Paris, New York, households underpin ‘good town’. The alternative, 60s, 70s and 80s suburbs, often (falsely) condemned as high density ‘sink estates’, prove to be unsustainable, segregated, sprawling, often cul de sac, disconnected, low density[2], bottomless pits of social deprivation and subsidy. If post-war council estates were viable market-places, the private sector would be there. Is it ever? Crime, maybe; drugs, maybe; social services and law and order, yes, at a cost. Business and development? Rarely – occasionally clinging on under tough conditions, abused for resultant high pricing (and worse).

Lasting ‘good town’ has higher population density, access to a rich range of resources, a simple, inter-connected grid of streets, walking route options to the many diverse needs, activities, jobs and pleasures that a residential population thrives on.

Town centres have even better and historic reason to anticipate social and economic viability. Qualities of activity, of footfall, of spatial integration, of access, of public space itself, give the private sector confidence to invest. Otherwise, developers seek to generate their own qualities of attraction – or create so-called ‘anchors’ and ‘magnets’, commercial imperatives rarely good for ‘town’ as a whole.

A local economy and those multi-varied ‘reasons to be there’ are vital components of sustainable towns and cities. The best tester of ‘good town’ is, ‘Is it visibly loved and used by local people?’.

Here, we set eyes on some Welsh towns, and offer occasional images.

Characteristics of our towns

The towns here considered [Figure 4] sit by fine, if rather understated rivers – crossing them being a substantial reason for their sustained historic existence.

Welsh names are a give-away: Swansea, at the mouth of the river Tawe – Abertawe in Welsh; Pontardawe, bridge over the Tawe; Bridgend speaks for itself (Pen y bont in Welsh); Glynneath tells you it is in the valley of the river Neath; and Port Talbot, a steel industry port of course, still toys with its former Aberafan name.[3]

Four of these have seen huge efforts of town centre regeneration; the other two, Pontardawe and Glynneath, are by-passed, given crumbs in compensation. The success rate may be measured by viability of resource providers and popularity of ‘people places’, by socio-economic vitality. Do please judge for yourself!

Our towns[5] of south Wales have much in common. There are, of course, obvious topographical characteristics, and diverse, often beautiful, settings. Port Talbot (and Aberafan) is coastal, flat, largely founded on heavy industry; Neath is a more typical valley town, further inland with a broader, less evident social and economic foundation.

The South West Wales’ city of Swansea has a centre still not rediscovered or convincingly reformed from the terrible bombing blitz of 1941 and subsequent ‘slum clearance’, having previously morphed from a world focus for copper, tin, and coal. Bridgend committed itself to ‘edge city’ growth, and now grapples with a future for its fine, under-achieving, residentially deserted centre. Glynneath and Pontardawe, having lost much of their industrial raison d’etre, like so many valley town comrades, yearn to rediscover their identity, or discover a renewed identity

Common characteristics of our towns include

Valuable efforts at varied town centre development, if still overwhelmed by motor vehicle culture. This applies to all these towns.

Centres, perhaps whole towns, unsure of where their heart is or, often, what it might be.

Reduction of vibrant public spaces, including streets, caused in no small part by diminished residential density.

Residues of traditional ‘town centre’ elements – indoor markets, churches, public transport systems, the increasingly rare ironmonger (a fine indicator!), from the days when people lived nearby. Town centre schools are a rare phenomenon these days.

Urban heritage, and tangible remnants of it, often undervalued and unseen by the white-hot heat of modern planning and development.

Relatively strong suburban communities, often no longer looking to the centre to meet social and economic needs.

Rich natural environmental settings.

Varied social and recreational facilities and continuing efforts to bring or strengthen activities. (Neath probably most evident, with it’s new Leisure Centre, barely integrated yet, but valuable; Swansea recently launched a new central entertainment Arena project.)

Valued and vital rail connections. (Not Pontardawe or Glynneath[6])

Recent catalyst town centre house-building/ apartments. (Neath again; Housing Association activity in Swansea centre has been impressive, recently superseded by high rise student apartments. That might be it.)

Of course, there is lots more. It is invaluable to be aware of this variety, these qualities.

The centres

How do the above criteria inform our understanding of these South Wales towns?

In summary:

Neath retains a remarkably varied retail and commercial base sprawling along (now one-way) Windsor Road, feeding round to Old Market Street – a rich canvas. Its indoor market is a dense treasure trove of local riches from meat and veg to knick-knacks.

Bridgend, still assumes a retail identity, despite investing hugely in ‘edge city’ retail and commerce.

Swansea, having lost its heart in the war, still seeks to change its historic evolved form, find its centre.

Pontardawe, by-passed, like so many Welsh towns, despite its long river-crossing history, makes do with a contrived ‘centre’, the real one subordinated to motor traffic.

Only Port Talbot, by good fortune, and Glynneath, by being left alone (largely ignored as its time in history elapsed), retain, despite everything, that most vital ingredient of urban renewal – a town centre residential population.

One fears for the impact of the pandemic on them all, not least due to the single-use, zoned (retail) planning philosophy used to justify urban reconstruction over the past 70 years or so, segregating homes, businesses and activities.

A significant commitment to a much-increased residential base in town-centres is the only sure foundation, helping consolidate footfall and demand. Whilst this is a social objective, combining people and homes with the daily resources they seek, it is also a pure, the best, business criterion.

What is to be rediscovered?

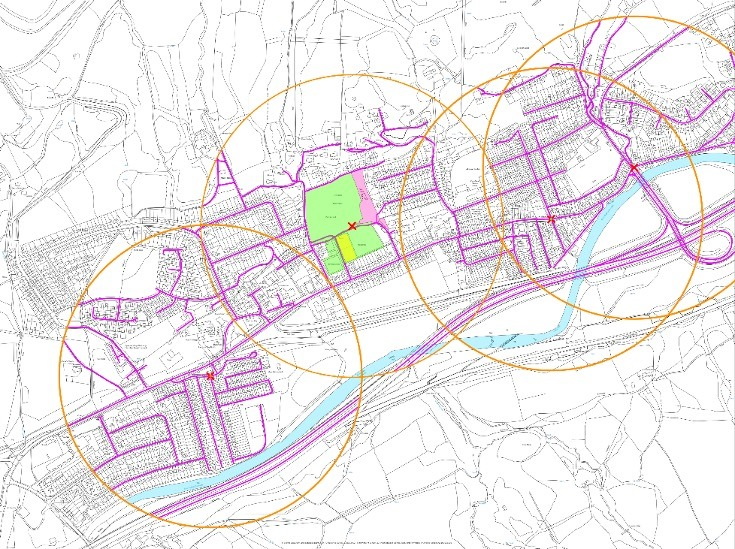

Glynneath retains that critical ingredient of urban vitality – a town centre residential population [Figure 5]

The five-minute walkability circles, show, on the left, a gridded residential community south of the old road, the greened Welfare Park surrounded by homes and, thirdly, the centre at the cross – solid gridded residential. Further right is the old cross, before the by-pass dual-carriageway on the south.

Upgrades should focus on the town’s much-loved assets, its resources – the centre, the park, the sub-districts, the potential growth spots, access to the fine river and hillside. Speeding cars are for the outskirts. The town is a rich canvas, much understated. As each ingredient is given attention, the priority, all along the main road, is to rediscover and redefine spatial characteristics at popular locations – for people, safety, greenery, speed reductions, business and recreation. These qualities and ingredients are to be positively shared between people, local people, and the motor vehicles that have dominated much of their space for too long now. Tilt now towards people – children, adults, older ones, disabled, on foot and bike. [7]

To benefit local communities, business and social vitality, upgraded public space makes visible a ‘shared surface’, integrated, local community nature of town – as it was before, but given a facelift! The focus is the High Street, Park Avenue, all of it, with pedestrian and environmental improvements at road junctions. There is no reason for that to be expensive in the first instance.

At the residential cluster in the south-west at The Chain [Figure 5], introduce planters, planting, surface changes and half-way refuge islands; also at the Lamb and Flag, the junctions to the Welfare Park and Trem y Glyn; at Lancaster Road shops and club; from the other end, the old cross by the bridge, perhaps that path down to the river; from all sides, the approaches to the centre at Heathfield and Oddfellows, and both north and south to the great assets of the Neath river [Figure 6] and the Gelli Cae Bryn wooded hillside walks.

In short, a lesson of note, the fundamental ingredients are there, established by history’s people-led adaptations, trial and error. First and foremost of the assets is a residential community. Then, the essential daily resources and activities – shops, school, recreation. They just need encouragement, and ‘spatial recognition’ to welcome locals and visitors to renewed, rediscovered pleasure and value of the town’s natural setting.

‘Open Sesame’. Discover the heart of Bridgend. Find magnificent buildings and public spaces, remarkably intact despite, perhaps thanks to, a political preference for car-driven, out-of-town development. An overwhelming road system and ‘edge city’ philosophy may have thoroughly distorted the way in which the town works but the local authority’s renewed vision for the centre makes a signifcant effort to stabilise its relatively substantial retail base. A wider mixed use palette of urban ingredients can only boost that aspiration, post-pandemic.

Bridgend’s central network of fine squares shouts out for revitalisation. Recent town centre regeneration initiatives require little more than inducements for people to come to the centre, some hopefully to live there. True, the spread of shops and restaurants might merit consideration, and each of the quality spaces, squares in particular, requires to enrich its active character.

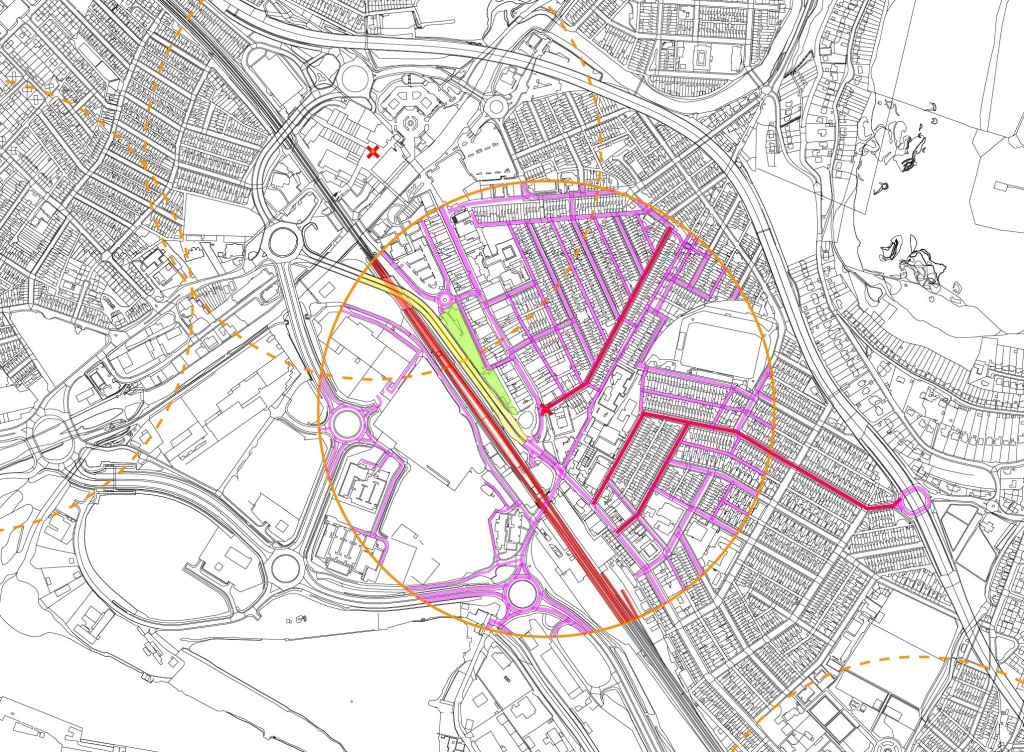

The plan [Figure 7] tells most of the story. The centre, remarkably, only about 150 metres square, is surrounded by the rail line and station (right), major roads (top and left) and car-parking bottom right. It is an almost perfect urban square of fine buildings and spaces – but …. very few people live there. What a canvas to work on!

Like Neath and Swansea, the town has an indoor market, here modernised, ‘mall like’, as was the trend in the latter half of the 20th Century. A planning and development focus on bringing back a residential base will boost the town centre’s riches, and the strengthened appeal of the college nearby (bottom right in Figure 7).

Bridgend’s fine centre perhaps has the finest set of close-knit public spaces and buildings of all those discussed here – the squares, the streets, the building history, the architecture. Truly excellent townscape ingredients are all in place – other than people!

Although an easy sound-bite, residential re-population is no mean challenge. On the other hand, the pandemic and the fragility of the commercial sector offer whole buildings, spaces over shops, changes of use and new development opportunities for a real chance of renewal. The Council itself, Housing Associations, and the private sector, can be encouraged by promoting the town’s excellent qualities and a renewed approach to revitalisation. Rediscovery. Encourage people to go back and live there. Older people who loved their town and would appreciate a short walk to the market and other resources. Younger starters seek affordable rented space near entertainment, recreation, public transport. Start moves towards provision of family housing in town – perhaps the education ‘hub’ could consider some school space.

Crudely, that is all it needs; Bridgend is a ‘Bart Simpson’ – a seemingly proud under-achiever. A reminder fundamental ingredient: People make places work.

The corollary is Port Talbot, just along the road.

A substantial residential population has survived in the terraced houses of central Port Talbot, despite the many 20th Century changes made to the town.

The inter-linked grid of residential streets, highlighted in Figure 9 (centred on the new ‘Transport Hub’), is remarkably intact. Down the road is a similar story in Taibach. In the other direction (top left) is the original Aberafan settlement.

These strong urban attributes of people, gridded streets, and density, are the template for all future planning – a most significant opportunity and starting point; urban riches largely neglected as all else was tried.

Only a few decades ago, that (even stronger) residential core for the labour of the steelworks and service industries, supported 17-pubs! Just think what residential density was there to support that amount of beer! And business. That town is gone.

Compare the urban ingredients of our circles to the sourrounds of the ‘modern’ 70s shopping centre (top middle x in Figure 9). Committed, the local authority moved its central offices there, a theatre, Tesco. Tied to the M4 motorway flying over homes, that was a fair old planning and development commitment, heavily motor vehicle influenced for parking and access off the motorway. Sure as fate, more cars and roads followed. From the west, to access the town, don’t try to sneak in the back way, unless in the know. No grid of streets here, turn back and do what you are told on the big roads provided.

Port Talbot was overwhelmed by the M4 – not unlike Boston, Prague, or Seattle, all now demolishing or reviewing their fly-over dominating urban form. For Port Talbot, new opportunities, on recently released former steel industry land across the rail line, are already predicated by car-led spatial organisation, to the detriment of 21st century planning. (Also Figure 9, left of rail line)

There is well-founded hope, if the powers that be can focus on town-making, rather than the seduction of ‘big new commercial opportunities’. Let’s just get the town in order.

A remedy is to hand. The new ‘transport hub’ draws attention away from the prolonged postwar experience at the Aberafan Centre [Figure 10], to find the rail station, a largely intact residential population, and the old ‘high street’ on Station Road – a main street; a well-structured street grid; a residential population; a tempting connection to the land across that rail line; a direct linear route to the reasonably healthy historic inner suburbs of Taibach and Aberafan nearby? Yes! These fine ingredients await a quite simple developer-funded rediscovery of town, based on a new social, commercial and cultural, central people place.

Shifting the heart of any town is not easy but the pre-conditions in Port Talbot are good. Existing ingredients support re-structuring. At the Square, Banksy’s fine local artwork, capturing some contradictions of the town, offers just one new ‘magnet’ to help make the square. Banksy is an asset.

The south facing frontage of the square awaits [Figure 11], albeit currently unsure of its place in the world, perceived as a bit problematic. A coherent long term strategy will change its image and provide confidence. There are available units, an exhibition to be built on, and homes. That side is the Square’s strongest asset, along with the rail station…. and the hotel… and the old cinema … and Station Road … and Talbot Road. Development on the west side will give everyone, especially the private sector, confidence.

A chunky residential development starting on the west side gable [Figure 12 and highlighted green in Figure 9] can make a central square at ‘the hub’. Three or four storeys high on that gable, with balconies and big windows, turning or sweeping round, will make a classy, south facing frontage replacing the car-parks. Currently, what passers-by and visitors see as they sweep in over the flyover is the carparks and the backs of the Station Road shops [Figure 13].

The central square will renew focus on Station Road – certainly deserving, and ask for consideration of Grove Place and Oakwood Street and how they bring (entice?) residents back to town. Eagle Street and Beverley, connecting to Tan y Groes, also merit enhanced streetscape invitations to the square. (These connections are highlighted in red in Figure 9 above.)

The re-location of Afan College adjacent to the station, over the line, will help focus on how movement across the rail line is to be resolved and will certainly encourage moves towards a more residential focus close to the transport hub and the town centre. The current pedestrian bridge over the rail line is a start. Build town across the way; welcome them to town, and rediscover the old link there. Figure 9′s walkability circle, centred on the square, demonstrates the scope for residential consolidaton across the railway line. Plenty to work on.

A new ‘Steeltown’ across the way demands a street grid, proper blocks, public fronts, private backs – not unlike the grids of the original town and of Aberafan. Find ways to link to new town on the other side of the rail line. Plan for that now; do nothing to impede it.

Like the others, Port Talbot’s ingredients are there – the rail station, the ‘high street’, the river, the link to the beach, the valley. Best of all: historic, traditional, rock solid residential communities are the foundation, short and long term. The task is ‘placemaking’ at the rediscovered centre, focused on the integration of local street grids, the boosting of the resource base and strengthening links to the many qualities of the town, river and coast.

A similar approach will revitalise Pontardawe, at its historic cross. Developer led work can dramatically boost both the ‘temporary town’ on Herbert Street [see Figure 14] and the old town’s future, and draw out the beautiful, understated, canal and river, the latter much abused by the by-pass road system.

Pontardawe’s core residential population is largely located in that top quadrant of the walkability circle centred on the historic cross. There, business still strives, largely in vain, to capture the local and passing trade markets that provided the town’s past commercial stability. The by-pass, (yellow in Figure 14) destroyed the business life of the town, further undermined by ‘big box’ retail and vast car-parking just a short disatance away.

The Herbert Street centre relies on that disconnected population, with the benefit of very limited passing trade. Businesses have proved remarkably resilient in the face of these overwhelming challenges. It remains tough.

Two remedies are, firstly, to consolidate residential life at the centre and, secondly, to pursue a longer term strategy of re-establishing the High Street.

An exciting starter is to build a three or four storey residential development on ‘brown-field’ land overlooking the canal (on land shaded pink in Figure 15). Not only desirable in terms of the integrated form of the town, such a development will boost both the current Herbert Street centre and stimulate opportunities for wider town rediscovery at the cross, not to mention the welcome to town visitors.

Development of quality, balconied, homes and affordable equivalents (perhaps for older retirees as a starter), with a bridged pedestrian route over the canal (perhaps two!) to Herbert Street and the Arts Square, is a golden, and much needed, recognition of the beautiful canal and river – just one of the town’s unsung environmental assets. [Figure 16]

The commercial viability of new development is considerable; the town benefit is immense.

The layout, north side of the canal, on that parking land, and its history, require much closer consideration but substantial apartments, plenty scope for parking underneath, residential frontage to the canal, views over the town, improved pedestrian routes, perhaps a new gardens, as well as the canal bridges, sound like quite a package for renewal – largely developer financed. Nothing is lost – the canal pathways are improved and parking remains, and there is everything to gain.

That space merits it, as does the town. Here is a town, a gateway to the wonderful Welsh country environment, that has a fight on its hands to retain and regain its character and integrity.

The task is to recognise the assets, use them to strengthen the town. For sure it needs a boost; the town and its residents deserve it

In Neath, the entire future focus is to renew outwards from ‘The Square’, the cross at Orchard and Green Street (the crossed centre of the walkability circle in Figure 17) .

Valuable improvements, in part recognising the old town, are underway, although the spatial dominance of Morrisons supermarket (at the bend in the river; lots of cars) will take some recovering from.

Neath centre is elusive. Is it somewhere on the ranging retail and commercial activity on Windsor Road (feeding in from the south, slightly left of centre) and The Parade, perhaps at that tempting junction with the rail station and Green Street (from the cross towards the rail station)? Or Morrisons’ vast hypermarket and carpark by the castle making a pitch for central dominance?

Figure 17 demonstrates that the old cross at Orchard Street and Green Street, stakes best claim, both by greater urban inclusion (less fettered by rail lines, canal and river) and a street grid revealing a connected urban history – the castle, old Market Street, the Gwyn Hall and the indoor market [Figure 18]. Initial improvements there certainly merit further encouragement.

Like Bridgend, Neath has a legacy of buildings to be celebrated and fine opportunities for placemaking. There is potential for ‘niche’ environments for restaurants (or clubbing?). (See Figure 19, from Glasgow) And, like the others, the challenge, already being addressed, is to bring homes, in good numbers, and varied household sizes back into town.

Why are our towns like this?

To bring these analytical threads together, we look to South West Wales’ administrative centre, the city of Swansea. Since WW2, in all the towns, motor vehicle movement has dominated town planning, albeit in the name of, and supposed servant of, retail.

Our first real focus on the impact of car domination was in Prague back in ‘93/4. Wilsonova, a vast dual carriageway, overwhelms the great urban richness of the Art Nouveau rail station, high density city centre homes, quality architecture all around, another rail station nearby, Vrchlicky Gardens, urban form to die for and, just round the corner, the Opera and Wenceslas Square. This was no communist aberration; they were not to be outdone by the west. (Figure 21)

All our South Wales towns followed the trend, as did most others.

Swansea’s ‘naturally evolved’ pre-war town [Figure 22, 1938] gathered three regional feeders – from Carmarthen in the west, Llangyfelach and north, and Neath in the east at the resultantly bustling Greenhill, top of the High Street (centre of top circle). That city backbone ran down to the town centre, just outside the original castle walls, where it was joined by the agricultural communities of Gower from the west. (The middle circle in Figure 22.) Further down, Wassail Square, centred the dense concentration of worker households serving the docks and rail lines.

That vibrant, no doubt tough and over-crowded, town centre was obliterated, first by the terrible blitz of 1941 and then ‘slum clearance’. The street plan was remodelled, thoroughly disrupting the old pattern. Repeated efforts have failed to establish or even identify a centre of town. Central dual-carriageways cleared vestiges of the old town missed by the Luftwaffe. Soon, a new road-link (south-eastwards in Figure 23) to Neath, Cardiff and England, completed the disruption of the naturally evolved spatial history and ‘organic’ morphology of the town. It was transformed for the motor vehicle. Terraced homes of docks and industry workers were cleared in favour of shops and offices, as in many British cities. Residents were moved to distant ‘garden city’ suburbs, there perhaps to gain a romantic pastoral ideal in new-built homes with baths and toilets, yet deprived of the vast range of town resources they had grown up with. (See Billy Connolly and endnote [8] below.)

The town’s already relocated great market was rebuilt after the war damage; ‘The Quadrant’ mall built, with Debenhams given a deal for pride of place; Tesco afforded a privileged location; ‘Castle Quays’ and St David’s commercial developments failed their promise. Meanwhile, the urban structure of the town, now a city, was reformed, bit by bit, road by road, without any real concept of where the centre might resettle. No acknowledgement made to the town’s magnificent setting on a fine river, a magnificent bay, surrounded by a virtual caldera hillside of woodland and glorious vernacular housing. Little homage was paid to these dream ingredients in post war regeneration.

The centre became what I call ‘Plas Heb Enw’, the place with no name (‘the Kingsway roundabout’, the centre of the circle in Figure 23). That spatial ‘centre of gravity’ has been conceived as a junction for motor vehicles, not people, ever since. The nearby High Street became a neglected, unloved, place. By-passed. Like Bridgend, Swansea’s centre was disconnected from its residents by an elaborate road system. Motor vehicle led planning similarly disrupted Pontardawe, dominated Port Talbot and focused on the super-store in Neath.

Only in Glynneath and Port talbot are walkable connections from homes to the daily needs the private sector is so willing to provide, still evident – at Heathfield and The Chain in the former, homes off Station Road, in Taibach and Aberafan, in the latter.

Coastal Housing has re-instilled some life to Swansea’s old central axis, with homes and culture-led regeneration, bringing the High Street and Wind Street (that winding route onwards to the south in both Figures 22&23) back from the brink. It remains a very tough commercial environment. Right now, Pobl is bringing affordable apartments to the very centre (at Plas Heb Enw – the circle centre on the 1979 plan), and some are attached to the current ‘City Deal’, Arena project. The return of mixed tenure/ mixed size households to Swansea centre is the city’s most urgent task of the 21st Century.

Homes will help the city rediscover itself, its vital streetscapes in High Street, Oxford Street, Kingsway and Princess Way, perhaps finding some historic names again – Gower and Goat Streets, Fisher, Rutland, Orange, Garden, Wassail.

The city yearns for family living and the door-step, rich mixed-use orientation of its past. The post-pandemic offers great opportunity. Rediscovery shouts out for itself.

Conclusion

The pandemic lock-downs transformed how we perceive our living environments – the spaces, the places, the resources, the air quality, the preciousness of nature. In towns and suburban centres, we learned to appreciate access to, and the viability of social provision. ‘Good town’ is sustained by hundreds, nay, thousands of people, people in homes. As we emerge from the pandemic, let us provide for younger people, ready to leave home; older ones, appreciating the heart of their town, able to walk to most needs and pleasures and maintain a degree of independent life. Families, children, schools, play, culture, the arts, parks, wildlife and the environment, transport, health, you name it, make places work.

Across the world, progressive cities are rediscovering themselves. Paris’ Mayor Anne Hildago promotes a ’15-minute city’, to much acclaim. The ingredients and aspirations are very much within our walkable city model. They are also the essence of what is called the ‘foundational economy’ here in Wales. The basic ingredients of spatial organisation have to be right. Welsh Government and local authorities in Wales are embracing the importance of central places and the mantra is now a ‘town centre first approach’. A ’20 minute place’ approach is on the table. None of this is new – the Victorians got lots of it right (why we’re still using Victorian infrastructure in so many instances) – yet ‘mixed-use walkable city’ was seen as heresy in our car-dominated, low density, sprawl-encouraging post-war planning environment.

Perhaps spurred by rediscoveries made during the awful events of the past year or so, we recognise the loveliness of sustainable town on our doorsteps. Or perhaps we learn to acknowledge the life difficulties of those less catered for.

The qualities of town that Billy Connolly was taken from in his early teens[8] are qualities that people, like me, love to experience in the great European cities, in London, Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow and Edinburgh, in Jane Jacobs’ Greenwich Village, in old Port Talbot, Swansea, Bridgend, and the others – town that people live in and love.

“Oh I was born in Glasgow, near the centre of the town; I would take you there and show you but they’ve pulled the building down.

I knew from an early age that I wanted to escape. It’s not that there was anything wrong with where I was; it was just that I wanted to be somewhere else. Then, when I was a teenager, it happened. I left, or to be accurate, I and tens of thousands of other Glaswegians left. We were told we were living in slums and they, and we, had to go. So we went – to a different kind of slum, in the country, called Drumchapel.

Now we all had indoor plumbing. Problem was we had fuck all else. When they took us there, there were no amenities. It was a crime to move thousands of people to a housing estate with no cinemas, no theatres, no cafes, no shops, no churches, no schools; just houses.

Being moved to a new house is a good thing, but not if that’s all there is. So you’d get up in the morning, go to your work, come back to your house, go to sleep. There’s something nasty about it; there was a dirty trick played on us.

One of the first things I ever remember feeling was being terribly cheated. The wee faceless councillors in Glasgow had dispatched us out here and we were supposed to feel great because we had a bath. But, you know, you can only spend so much of your time in the bath playing with your rubber ducks and things.

Even as a boy I knew cafes, cinemas, community, were the key to a sane life. If a place has none of those things, a dullness descends, a kind of anger develops and if you have no way of articulating that anger, you just lash out. And the architects of this brave new world? – town planners in Georgian houses.

But for every ying there is a yang. And while my memories of Drumchapel weren’t all good, they weren’t all bad either. I was a teenager [I was 14 when we moved there] becoming a man ….”

New developments, building conversions, homes above shops and more, will help retain and revitalise urban character and the qualities loved by locals. This is particularly true for the big towns of Bridgend, Neath and Swansea. Port Talbot has its challenging opportunity across the rail line.

People and vibrant places give confidence to the private sector. Barcelona’s people-oriented placemaking in the 1980s revitalised the city. Bloomberg’s Highline and riverfront parks of the noughties in New York, generated an almost frenzied commercial response. ‘Starter ingredients’ are there in our towns – natural assets like Pontardawe’s canal, Bridgend’s squares, Swansea’s river, bay and fabulous history, Glynneath’s river and hillside woodlands. And valuable new ingredients – Neath’s central streetscapes; Port Talbot’s new central focus. There may well be more ‘working from home’ but that is no reason to get into the car for everything else. ‘Good town’ provides it all.

Post-pandemic times yearn for innovation and variety, rediscovering the varied people-oriented mixed-use offerings of our urban past. And our future.

The litmus test? Are local people there? Look, listen and linger in Swansea, Neath or Bridgend markets. Locals love to be there. Young people love to pub and club in Swansea’s Wind Street. These magnet ingredients merit their upgrades, understanding them to be just one part of the make-up of good town. Paradoxically, towns with a sound residential base (Port Talbot, Pontardawe, Glynneath) get too little such attention, so little tlc, so few treats. Locals flock, instead, to rare events at ‘people places’, to monthly street markets, annual festivals, local fetes. They love to partake of vitality in their towns.

Our collective responsibility is to rediscover the vitality and variety that nurtures our urban centres, to encourage people to stay, to enjoy, yes, to love, their towns.

End

[1] Jacobs, Jane,The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Penguin, 1961, ‘Illustrations’ in forewords.

[3] See Jane Jacobs (ibid) on ‘density’. For further discussion see https://4cities.wordpress.com/2010/06/18/residential-density-people-homes-and-numbers-in-bustling-manhattan/

[4] You’ve learned enough Welsh for that one already!

[5] Swansea became a city in 1969. Here, for convenience it is referred to as ‘town’.

[6] Finally axed by Beeching in 1964 but certainly undermined by the decline in the coal industry.

[7] Further discussion on Glynneath can be found on the Urban Foundry Website https://www.urbanfoundry.co.uk/

[8] On council housing in the 50s and 60s: From Billy Connolly: Made in Scotland, Series 1 Episode 2 BBC iPlayer

Acknowledgements.

The discussion arises from a outline commission carried out by Urban Foundry for Neath Port Talbot Council in four of the towns, in which we have been working. Thanks to them for what proved to be a most stimulating study. Public versions will be available in due course, and links provided on the Urban Foundry site https://www.urbanfoundry.co.uk/

Images and text are credited as appropriate, mostly via Urban Foundry, but special thanks go to Tara Tarapetian for the plan images and joint studies, and to Ben Reynolds, who oversees the wisdom of words and himself revels in our work to assist communities in Wales and beyond.

The work derives from and still draws heavily on theory developed at The Joint Centre for Urban Design at Oxford Brookes University, way back then, with Steve Thorne https://spacesyntax.com/staff/steve-thorne/ and others.

Personal support, ‘lay’ constructive critique and multiple readings are gratefully provided by my long-time partner Deb Checkland, who sometimes senses my deep appreciation.

Responsibility for all this remains entirely with me, of course. Thanks to all.

Your post inspired me to look up each of these towns on the excellent ‘Understanding Welsh Places’ site, which is a treasure trove of social and economic data, though I didn’t find out anything particularly surprising.

Bridgend stands apart from the others with a younger and better-qualified population, a diverse business base and lots of in-commuting. If the rest have anything in common it’s major commuting outflows (usually by car). Pontardawe and Glynneath are essentially rural towns – Glynneath is really just a village with fewer than 5,000 people. Neath seems to be slightly better off than Port Talbot on many indicators though they both have lots of homeowners and more people born in Wales than the average. I’m leaving Swansea aside as unlike the others it is a city, has universities, more single people, more service sector employment and other socio-economic differences.

Perhaps we shouldn’t lump these five towns together given their different geographical settings and roles in the urban hierarchy, but when looking at the specific issue you raise of residential development in town centres I do think there’s a common challenge – who is it for? We know the appeal of city centre living is proximity to (a) jobs and (b) amenities, which attracts young professionals in particular. Your average Welsh graduate is keen to move out of Neath or Bridgend and sample the bright lights of Cardiff in their 20s. This kind of phenomenon explains why the Centre for Towns found that British towns have been ageing over recent decades while the big cities – including Cardiff – have been getting younger.

Those 20something graduates may well move back to towns in their 30s of course, though probably in search of a bigger home with more green space and less noise – i.e. probably not in the town centre (unless it is redesigned very radically to offer both of those in competition to your average suburban semi). So that leaves us with residential development for retirees and social housing. Obviously both have their place in town centres but they aren’t, on their own, a panacea for regeneration – many of these residents will inevitably be low income, and you presumably want as broad as possible a social mix in any vibrant town.

None of this is to say good urban design has no place or is fruitless in the face of broader demographic and housing market trends, but we do have to think about the role of these towns, individually, in the wider region. What works in Glynneath, a village 20 miles’ drive from Swansea, might not be right for Bridgend, a large town 20 minutes’ down the railway from Cardiff… and vice versa.